HuffPost Blog Posted: 04/03/2014 7:35 am EDT Updated: 04/07/2014 3:59 pm ED

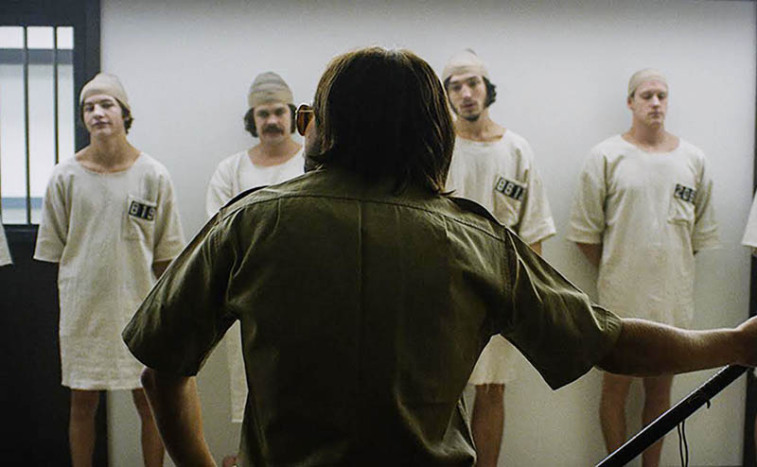

Popular culture has offered some flamboyant, unrealistic images of the psychopath: the giggling, twitchy maniac; the silent, masked slasher; the snobbish, culturally refined, highly intelligent cannibal and–depending on how much you like your job–your boss.

Another potentially misleading image appears in the recent trend to imply that anyone with some psychopathic traits is a psychopath. For example, in the eyes of some, a surgeon with a rotten bedside manner, and no inclination to weep with sympathy as he cuts you open to repair your faulty heart valve, nudges his occupation higher on the list of “professions with the most psychopaths.” An alternative view suggests this person might be an ambitious, no-nonsense professional, with limited people skills, who wants you to live. He studies for years, trains diligently, and ends up operating on you to repair your faulty heart and extend your life.

A psychopath does have not a few psychopathic traits. He or she has, as the Society for the Scientific Study of Psychopathy explains, “a constellation of traits.” And the image outlined by that constellation doesn’t evoke confidence over the long term: lack of empathy and guilt, an inability to form meaningful emotional bonds; narcissism and superficial charm; dishonesty, manipulativeness, and reckless risk-taking. Risk-taking is tolerable in surgeons. Reckless risk-taking is not.

The well-validated Hare Psychopathy Checklist-Revised is the best known tool psychologists use for measuring psychopathy. It’s dominance in the field is being challenged, but it has the advantage of not relying entirely on the psychopath to report on him- or herself. The PCL-R considers 20 personality traits and behaviors. It considers evidence of other traits and features in addition to the familiar listing of callousness/lack of empathy, lack of remorse or guilt, grandiose sense of self-worth, glibness and superficial charm, pathological lying, conning/manipulative behavior, and shallow emotions. It also rates failure to accept responsibility, need for stimulation, parasitic lifestyle, lack of realistic long-term goals, impulsivity, irresponsibility, poor behavioral controls, early behavioral problems, juvenile delinquency, revocation of conditional release, criminal versatility, promiscuous sexual behavior and many marital relationships.

When enough of these traits are present to a high enough degree, an outline of the psychopath emerges. The emerging outline, however, should not include any of these common misconceptions:

1. Psychopaths are insane.

The American Psychiatric Association considers psychopathy (which it equates with sociopathy and antisocial personality disorder) to be a personality disorder, while some people regard it as a personality type. Both agree that psychopaths know the difference between right and wrong. Legally, psychopaths are not insane. They do not hear voices or experience other hallucinations. Their thoughts are not disordered or skewed by delusions. In other words, they are not psychotic, a feature of mental illness.

2. All mass murderers are psychopaths.

A frequent response after telling someone that I was writing a book about biological studies of criminal psychopaths was: “You should write about [fill in name of mass murderer].” I often explained that psychiatrists had determined that the person they named was mostly likely psychotic and not psychopathic. Sometimes the response was puzzlement, sometimes understanding, and sometimes indifference. Most adults who kill multiple people during a single event are suffering from psychosis and have had a history of psychiatric illness. That is the conclusion forensic psychologist J. Reid Meloy reached after studying many of the mass killings that have occurred in the last 50 years. Most mentally ill people, of course, are not violent, but the lurid, over-coverage of these rare events by the media makes them seem like weekly occurrences. A minority of mass murderers includes depressive homicidal individuals, and very few are psychopaths like Columbine shooter Eric Harris.

3. All psychopaths are violent.

Psychopathy is a risk factor, but not a guarantee, that someone could be physically violent. That is not surprising if reckless risk-taking is combined with lack of empathy and guilt, and an inability to form deep emotional bonds with other human beings. You might not want to hang out with someone with these traits and you certainly don’t want to share a situation in which resources are scarce. But the collection of traits and behaviors that characterize psychopaths leaves plenty of room for nonviolent lifestyles.

4. Prisons are full of psychopaths.

Prisons are not full of psychopaths, but they are full of people with antisocial personality disorder. Although the American Psychiatric Society still equates psychopathy with antisocial personality disorder, the majority of psychopathy experts do not. Antisocial personality disorder is diagnosed based on antisocial acts and behaviors. Not surprisingly, most–75 percent or so–of the folks you will meet in prison qualify for this diagnosis. As outlined in the introduction, a diagnosis of psychopathy is based on more than the antisocial behaviors used to identify someone with antisocial personality disorder. Approximately 20 to 25% of prisoners are psychopaths, according to estimates by psychologists.

5. Boardrooms and Wall Street are teeming with psychopaths.

Despite media accounts, psychopaths are not swarming the financial district of New York or the offices of corporate America. Unfortunately, the less than teeming numbers may be more than enough to seriously inconvenience the rest of us. A preliminary study by psychologist and business management consultant Paul Babiak and his co-authors found that eight of 203 corporate professionals taking part in management development programs scored high enough to be classified as psychopaths. This 4 percent is indeed four times the number found in the general population. Testing of larger, more representative groups, of course, could yield different results. But the irresponsible behavior of remorseless, empathy-deficient, conning members of the financial community– remember 2008?–has convinced many of their victims that we need to do more to understand such behavior and prevent it. Psychologists who study corporate psychopaths do not downplay the damage a relatively small number of psychopaths can do in their organizations and to society.

6. Experts agree on the nature of the psychopath.

There is little disagreement among experts about the presence of psychopathy in certain individuals. One classic example is the criminal who scores high on the Hare Psychopathy Checklist. These people show mean, callous, remorseless, coldblooded, and aggressive behavior. These are the rare folks FBI profilers encounter on the job.

Disagreements among experts start to emerge when the concept of psychopathy is extended to other populations and when newer, different measuring tools are used to identify them. Subtypes of psychopaths such as successful versus unsuccessful, and primary versus secondary are discussed but still very poorly understood. Should a cold-hearted, empathy-deficient, callous and emotionally shallow person share the label “psychopath” with a cold-hearted, empathy-deficient, callous but anxious person? Should the label be reserved for extreme cases? Or can the elements of the constellation of psychopathic traits be present in different degrees and combinations to yield a variety of problematic, and some less problematic, personalities we have hardly begun to explore?

As psychiatrists Samuel Leistedt and Paul Linkowski conclude in a recent Journal of Forensic Sciences article, Psychopathy and the Cinema: Fact or Fiction?, “Although we are able to describe the psychopath fairly well, we do not understand him.”

Dean A. Haycock is the author of Murderous Minds: Exploring the Criminal Psychopathic Brain: Neurological Imaging and the Manifestation of Evil published by Pegasus Books, 2014.

Follow Dean A. Haycock on Twitter: www.twitter.com/Dean_A_Haycock